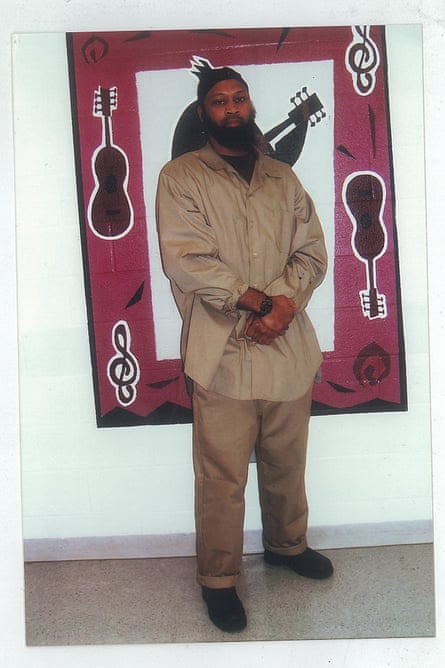

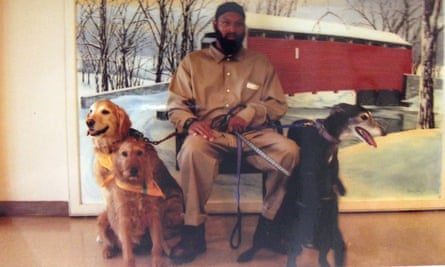

It’s hard to imagine Steven Northington killing two people. The 43-year-old says he likes to make people laugh, “like a comedian”. He’s a loyal son to his troubled mother and father. He sends his younger sister birthday cards from prison and draws elaborate smiley faces on them. His defense team laughs with affection when they hear his name because he is, they say, “a character”.

Between 2003 and 2004, Northington was slinging for a drug ring that flooded his Philadelphia neighborhood with bloodshed. The Kaboni Savage Organization was responsible for nine murders during those two years alone, including the firebombing of a house that killed two women and four children.

The government was after them, and they knew it: seven of the nine victims were murdered in retaliation against witnesses who had agreed to cooperate with prosecutors to bring the kingpin down, according to the FBI.

It wasn’t until 2013 that the federal court started its trial against ringleader Kaboni Savage, as well as his sister Kidada Savage, accomplice Robert Merritt, and Northington. The four were tried together for a total of 12 murders dating back to 1998.

Northington stood apart because he was arrested a month before the firebombing, and only charged for two of the murders – those of Barry Parker, a corner competitor of the ring, and Tybius Flowers, a childhood friend. In Flowers’s case, the execution happened hours before he was supposed to take the stand as the star witness against Savage in a 1998 murder case.

Northington was convicted by the state court in Philadelphia in 2007 for the murder of Parker. In 2013, the federal trial combined the two murders and found Northington guilty of aiding both.

And since the murders were an attempt to intimidate witnesses and in support of racketeering, federal prosecutors wanted him dead.

They asked for the death penalty.

Days before he was sentenced, one of Northington’s lawyers, William Bowe, showed the jurors something they never saw during the six-month trial: images of Northington’s brain. He told them that Northington was developmentally stunted by homelessness, abuse and prenatal exposure to drugs and alcohol.

Bowe said the deficiencies the scans revealed provided some explanation for Northington’s actions – not an excuse, but an extenuating set of circumstances.

“What does that mean? It means that Steven Northington doesn’t think like you and me. It means his brain doesn’t function like ours. It means when he makes a decision, he doesn’t do it like you or me. It’s broken,” he told the jury.

Brain images are becoming standard evidence in some of the country’s most controversial and disturbing death penalty cases. In March, Barack Obama’s bioethics commission released a report stating that neuroscience is used in about a quarter of capital cases, and that percentage is rising quickly.

Lawyers use scans in a few principal ways. Sometimes it’s to explain a psychiatrist’s diagnosis to help a plea of insanity, or to help prove intellectual disability. Most often they are used to ask juries for mercy during the sentencing phase of the grimmest trials.

Since the inner workings of a criminal’s mind are central to a case, any tool that might shed light on the 3-lb organ is worth considering. And brain scans have diagnostic credibility: they are fundamental in clinical settings for spotting tumors, cancer or traumatic injuries. They have been used to study aspects of behavior, such as decision-making, depression and impulse control. But in death penalty cases, the images are taken out of that medical or experimental context, and used to clarify nuances of criminal actions.

It remains unclear whether pictures of neural processes or of brain anatomy can reveal a person’s morals or the substance of their character. But despite incomplete science, brain scans are becoming crucial arbiters of life and death.

The first criminal to use brain images for his defense was John Hinckley, who at age 25 shot president Ronald Reagan and three other people in 1981.

The defense team argued that Hinckley was mentally incapacitated when he fired the gun because of his severe schizophrenia and depression, and hence should not be held responsible for the crime. They contended images of his brain supported that diagnosis.

The judge permitted David Bear, the psychiatrist who diagnosed Hinckley, to exhibit a CAT scan of the outer layer of his brain.

Bear said Hinckley’s sulci, the medical term for the valleys that run across the cerebral cortex, were wider than average; he cited a published paper correlating wider sulci to schizophrenia (this observation has not changed over time: some people with schizophrenia do indeed have wider cortical grooves – but so do many people who are not schizophrenic or suffering from any other mental disorder).

Neurologist Dr Helen Mayberg of Emory University, known for her work on depression, said during an interview that Hinckley’s case demonstrates fundamental problems that brain images bring into the courtrooms.

Mayberg, who is often paid by the prosecution to cripple a defense team’s brain imaging science in high-profile cases, said that if Bear had not diagnosed Hinckley with schizophrenia, the scan would not have meant anything. And conversely, if Hinckley’s brain had appeared normal, it would not have negated Bear’s psychiatric diagnosis. “The guy was psychotic,” she said, regardless of the scans.

If the same trial took place today, she said, the technology would be newer but the argument the same: a neuroscientist would say that parts of Hinckley’s brain has traits that some scientific papers could correlate with some mental disorder. But unless the scan shows something like a tumor, they are never powerful enough to diagnose. “The irony is, using imaging evidence just obfuscates the issue,” she said.

Hinckley’s defense team used a CAT scan in 1981 – just two years after the producers of the technology had been awarded the Nobel Prize. But MRI scans soon replaced CAT scans: an MRI can see right through the bone of the skull, whereas a CAT scan cannot.

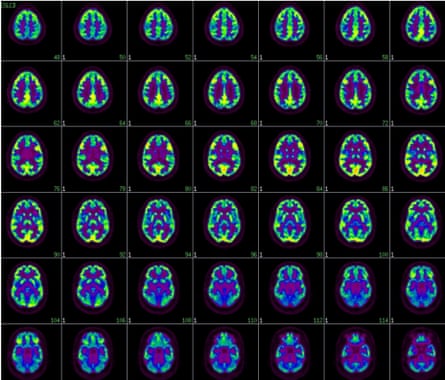

By the early 1990s, expert witnesses were showing PET scans, which record the brain’s metabolism. PET maps where the brain is burning glucose for energy, which is interpreted as bursts of neural activity. The subject has to be pumped with a radioactive glucose tracer; when the brain metabolizes the glucose it emits photons, which are recorded in color: flaming yellow often means the brain is burning more glucose, blue means the opposite.

Hinckley won the insanity defense with the CAT scan, though its weight on the verdict is unclear. Mayberg and others argue that it was insignificant to the insanity plea. At the time, it was up to the prosecution to prove Hinckley sane – after the trial, jurors said in news reports the government had failed to do so.

Regardless, the verdict led to a revolution in how the courts evaluate mental health and changed the standards in federal court. Upheaval over the decision prompted Congress to alter what defendants had to prove to be acquitted on grounds of insanity. The federal government and many states also shifted the burden of proof to the defense, which raised the bar for lawyers seeking an acquittal based on mental incapacity. And since then, advances in neuropsychological science have become more attractive to defense attorneys.

Northington’s lawyer said he has noticed that over the last 20 years defense teams are also being held to a higher standard. “What constitutes effective counsel has become much more rigorous,” said Bowe. “As that becomes more rigorous, the courts are essentially telling the lawyer, ‘You’ve got to look into all this stuff.’ So I think there has been a natural growth and it’s naturally going to lead to more brain imaging and scanning.”

The Bioethics Commission cited a report that analyzed 1,586 judicial opinions that used neurological or behavioral genetics evidence between 2007 and 2012; 40% of them were to defend the death sentence, and 28% were to compensate for ineffective counsel.

Northington and his two older brothers grew up nomadic; they lived in train stations, homeless shelters and hotels. Their mother was around, but they were often left on their own without food or money. In 1987, he was in seventh grade at age 15 and had 138 absences that school year. He had been held back in first, fourth, and sixth grades.

His long relationship with the legal justice system started one year later. He was arrested for possessing a controlled substance, as was his mother in a separate case that year, but both their charges were dismissed. His mother, Annette Northington, recently said she started smoking crack around that time, and had turned to prostitution to support the habit.

“That area, when you move in there, it’s like you’re entrapped,” she said of their Philadelphia neighborhood. “If you didn’t know what was going on you would have thought they were giving out free food, that’s how long the drug lines were. And I never thought it’d be me standing in that line, and I ended up one of them. So it’s not a happy story and it’s not a good story but it happened to me and I regret it.”

She said she had named her son after her brother Steven Northington, who was sentenced to life in prison when he was a teenager. “I remember I named him the same name as my brother and I was thinking please don’t let this be like a whammy or something … and it’s just like a nightmare.”

At 18, Northington was convicted for the first time for aggravated assault and robbery. He was sentenced to five to 10 years with a chance of parole. In 1991, the court had ordered Northington’s first mental evaluation. An investigator found that the government psychiatrist diagnosed him with Paranoid Personality Disorder, but did not recommend treatment because he was “particularly distrustful”.

Instead, Northington spent most of the last seven years of his sentence in solitary confinement – 23 hours a day alone in an 80-square-foot cell – as punishment for more than 100 disciplinary infractions. Most of them were for nonviolent breaches, such as refusing to take orders, spitting, cussing or outbursts, while some were assaults that included kicking and throwing feces.

In 2000 he maxed-out his sentence and was released to the neighborhood he knew best, without a home. During the next two years, he was rearrested twice, the second time costing him seven months in jail because the government had mistakenly thought he was violating his nonexistent parole. He was released again around May 2002, less than a year before Parker was shot to death.

By introducing brain scans, Northington’s lawyers were hoping to show that he was intellectually disabled. If they could prove it, the court would not be able to punish him with death, even if he was found guilty. In 2002, the US Supreme Court had ruled that it would be cruel and unusual punishment to execute a person with such an impairment. He or she can still be found guilty for the crime, but not killed for it.

The ruling was left to the judge, who had to decide before the trial began whether Northington was intelligent enough for the death penalty.

At that time the court was using a revised version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV, or the DSM IV-TR, as one of a few guides to define someone with intellectual disability: an IQ of approximately 70 or lower, with trouble learning or intellectually functioning since youth (the newest version of the DSM puts less emphasis on IQ, but still cites a measure of approximately 70 or below). Northington’s lawyers wanted to use brain images to meet the criteria by showing he may have had severe mental setbacks while growing up.

They turned to Dr Ruben Gur, a leading neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania. The director of the Center for Neuroimaging in Psychiatry and Brain Behavior Lab, Gur testifies in many courtrooms about how brain scans might explain a criminal’s behavior.

His wife directs the Neuropsychiatry Section of the Psychiatry department from an office just across the hall from him. One of her latest cases entails the psychiatric evaluation of James Eagan Holmes, the man who said he thought he was the Joker when he killed 12 people at a Batman screening in Colorado.

In 1997, Gur and his wife were asked to analyze Ted Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber. It was their first criminal case. “We spent a nice weekend in Helena. I tested him and Raquel gave him a psychiatric interview,” Gur said during an interview in his office.

Gur said he would never work for the prosecution; since he is among few doctors in the country who can analyze scans the way he does, he feels obliged to protect people who may have mental ailments, not work against them.

Mayberg is his nemesis: she thinks Gur lets his opinion about the death penalty cloud his scientific testimony.

Mayberg often argues that no scientific data can support what Gur says in court, while he often says he is not diagnosing, just emphasizing correlations (they both charge $500 an hour for their expertise).

Their differences are most apparent when they talk about their roles in the 2007 Lisa Montgomery case. Montgomery had been accused of strangling a pregnant woman to death, then cutting the baby out of her womb. Montgomery’s lawyers were trying to win the insanity defense. They said Montgomery could not be held responsible for the crime because she was so mentally unstable when she committed it that she could not understand it was wrong. They argued that she had a rare mental illness called pseudocyesis that made her believe she was pregnant.

Before the trial, the judge had to decide whether the lawyers could use her brain scans as evidence in the trial. Gur, who was testifying about their validity, said the scans showed that Montgomery suffered from functional abnormalities that could be consistent with that diagnosis. He singled out her hypothalamus, an almond-sized hormonal regulator in the core of the brain, because the PET showed that it was overactive. He cited a scientific paper from 2006 in which a biology student had stimulated female rats. The stimulation had caused their hypothalamuses to release hormones and physiologically prepare for pregnancy.

Mayberg, for her part, said it was inappropriate for him to be relating Montgomery to rats. The judge agreed that the science was irrelevant and excluded Gur’s testimony from the trial.

Montgomery was found guilty, and sentenced to death.

Testing the brain of a defendant is a rigorous and expensive practice that, in federal cases, requires the judge’s permission. The scans alone can cost around $6,000 and then experts are paid to analyze the results and testify in court; Mayberg and Gur say their bills are on average about $10,000 for 20 hours. Northington’s request was approved, but lawyers say it’s not always easy: in their experience, it depends on the jurisdiction.

After weeks of memory, spatial, speed processing and other performance tests, Northington was escorted to a hospital by prison staff. Technicians there performed the scans in two machines – MRI and Pet devices.

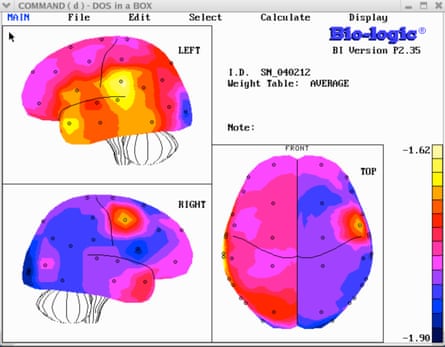

Gur brought his analysis to the stand during Northington’s five-day pretrial hearing: he said Northington’s brain was oversized and out of balance structurally and actively; flaming yellow areas were overcompensating for blue ones.

He walked the court through Northington’s brain piece by piece, emphasizing each element that looked too big, too small, over or under active. He said the hindrances could have affected his capacity to control himself, his motivation at school, and his ability to read or comprehend spatial layouts. All of it, Gur said, was likely from a blow to the right backside of the head and exposure to alcohol while his mother was pregnant. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum disorders are the number one cause of intellectual disability.

Two doctors also testified about Northington’s IQ. The defense found it was 67 and the prosecution found it was 64, but argued that he had sabotaged the tests on purpose.

After that testimony, Northington told the judge he was tired of being harassed by the prosecutor and asked if the judge could get him out of solitary confinement, or “the hole”. “I need to be in population. It’s messing with me. It’s messing with me. I’ll do the test all over again. I don’t care. I want to go to trial. You can give me the death penalty. I want to go to trial. I want to prove my innocence. That’s it. I got rights,” he told the court. Northington’s defense lawyers say the judge tried to help accommodate Northington, but that he remained in and out of solitary.

A couple weeks after the hearing, the judge, in a 61-page statement, said that there was not enough evidence to convince him that Northington was intellectually disabled.

“With respect to the neuroimaging data, while [the Court] find[s] that the data demonstrates that areas of the defendant’s brain are functioning abnormally, Dr. Gur’s testimony did not convince the Court that the totality of the defendant’s brain abnormalities would lead to a diagnosis of sufficiently sub-average intelligence.”

The decision triggered the start of the trial with the death penalty looming.

Northington’s mother said she watched almost every day of it. She traveled back and forth from court to the hospital because her oldest son Michael had colon cancer. In 2011 she had found her youngest son, Kadrice, dead at 35 from a drug-related heart attack. Five years before that, her other son Jamal had been shot to death by a robber at 25.

Shaken by the prospect of Northington’s execution, Annette Northington said she prayed for help when she left the court the day the jury found him guilty. “I was [going] home all the way with tears knowing that my son was facing the death penalty, thinking ‘Dear God, what is it that I can do ... they gonna kill Steve.’”

If a murderer is convicted and the crime is punishable by death, the trial moves on to the penalty phase where the same jury hears about the defendant’s background before sentencing. This is the most common way lawyers in criminal courts use brain scans: to mitigate against the death penalty.

Since the defendant has already been found guilty, the jury has to answer the gravest question: should he or she die? And because it is a person’s life, lawyers bend over backwards to bring science or other evidence into the courtroom that might otherwise not be permitted. It is the defendant’s constitutional right to show their arbiters every piece of evidence that could sway that judgment, even if the science is premature.

This phase can free scientists from the thorough peer review that otherwise validates their theories. When neuropsychologists, such as Gur, are asked to testify, it is because they are esteemed within the field and have published scientific papers that have been meticulously vetted by other independent scientists. In other parts of the trial, these experts can only testify about what has been published in journals, but in the sentencing phase, these same scientists are asked to make novel leaps or educated guesses. Gur has published more than 350 papers that often depict differences in people’s brains, but none of them identify behavioral markers in criminal minds or test the hypotheses he makes about individuals in court.

This time, because the rules are more relaxed, Gur was able to paint a picture of how the damage he found might affect a person’s character and intellect. “Such an individual can run into trouble on several counts … It’s likely to lead to bad decisions and difficulty to adjust behavior to the context,” he said. “Somebody with that brain would be vulnerable to talk out of turn, tell off-color jokes in the wrong company, not being able to adjust ...” He also implied Northington was vulnerable to coercion. “It turns out people with frontal lobe damage tend to respond very well to authority and to structure … they almost naturally gravitate toward somebody who will tell them what to do.”

Mayberg, who was not a part of Northington’s case but read the testimony, was appalled by Gur’s interpretations. “Clearly it’s not good to have a mother that drinks when you’re in utero. It is not good to be in a home that is poor. That said there are people who have those same experiences and become very successful. You can spin that either way,” she said. “He doesn’t speak to data, he doesn’t speak to literature, he makes it up. He interprets as he sees fit in a given case and makes inferences that are his alone.”

It’s not hard to deflate testimony about behavioral brain scans in court, especially at the sentencing phase. Academics have written many papers that explain why group level data does not accurately represent an individual. Scientists in forensics also ask whether it is appropriate to compare a supposed criminal’s brain to a dataset composed of the brains of healthy people. People with criminal records may have caused damage by doing drugs or getting into physical fights, while people within the control group are less likely. Since it’s rarely clear what caused which deviations, it’s also unclear to what extent the defendant should be held accountable.

Lawyers trained in neuroscience also argue that there is an undeniable difference between a hospital and the scene of the crime. They ask how scientists can be sure a brain scanned in a machine would look and operate the same way if it were scanned while the person was committing the crime. The defendant’s brain is often analyzed years after the crime was committed – Northington was scanned in 2012, the murders were in 2003 and 2004.

Limitations are rarely discussed in media reports, which tend to embellish new brain studies. Sensational news may have a powerful influence on judges and juries. Executive Director of the Bioethics Commission Lisa Lee said this type of misleading information has the power to affect important legal decisions, such as who should get the death penalty. “Headlines are just crazy about what neuroscience can and cannot do,” Lee said. “Given what’s on the line, it should be something we pay close attention to in terms of hype.”

These studies are coming from a newer, more accessible technology called fMRI, which is seen as less credible than PET. fMRI illustrates gushes of blood and is more attractive because it produces results faster and without a radioactive tracer, but it’s unclear how blood rushes relate to brain function. Regardless, fMRI literature is growing so fast that if death penalty defendants bring it into court, there’s more room for it to backfire. Defense lawyers already run the risk that scans will just convince juries that there’s no cure, that the defendant will keep committing crimes.

With fMRI, prosecutors will also have access to studies that can emphasize that mentality, such as one that predicts recidivism by measuring blood gushes in a limbic system linked to impulse control. Gur only uses PET for testimony because it’s what the court accepts, though he switched to fMRI for his own research many years ago. A judge in 2009 allowed an expert like Gur to testify about the results from an fMRI during sentencing, though he didn’t let the jury see the images.

“This is where it’s headed,” said Gur. “But you need to have a brave lawyer who is ready.”

When the time came for Gur to testify for the second time in Northington’s case, he did so for the jury, amid about a dozen other mitigating witnesses, including Northington’s mother, Annette.

She told emotional stories about being poor, reckless, homeless, in abusive relationships and disappearing to speakeasies or crack houses while Steven and his siblings were growing up. She said that she never visited or wrote to Steven those first 10 years he was in jail, and that she didn’t recognize him when he returned to the streets.

Another psychologist familiar with trauma also testified. He had evaluated Northington, his academic record, his family, history of solitary confinement and criminal record, concluding that Northington was a victim of trauma and mental health issues that were exacerbated by prison, yet never addressed. A special educator familiar with Northington’s old school district found that it failed to provide Northington with special education services while he was there; he had not received the support he deserved.

Over six days, lawyers questioned many more witnesses, including Gur, helping them describe to the jurors a caring man who was manipulated by Savage, and was being held more accountable than bigger players in the drug trade despite a sea of setbacks.

Then the jury heard closing arguments and went to deliberate.

“When [the jury] came out…I could actually see their eyes looking directly to me and I knew then that they weren’t sending my son to the death penalty,” said Annette Northington. “I just touched my grandson’s hand and he was really nervous ... and they said they sentenced him to life and then my heart just got like you know, I felt a little free.”

They unanimously decided the death penalty was too harsh. As for Savage, he was sentenced to death; his sister Kidada Savage and Merritt were both sentenced to life.

When Gur was asked about the outcome of the case he said, “we won.” But teasing out the role of the brain scans is tricky. None of the 12 jurors thought Northington had organic brain damage before the year 2000, which means they probably didn’t think he had it in 2003 or 2004. Ten of them thought he had organic brain damage at the time of the verdict. And while only one of them thought he was mentally ill, they all agreed he had symptoms of mental illness and that his “brain damage and/or mental illness made him susceptible to the influence of Kaboni Savage.”

Until recently, Northington remained in solitary confinement at a federal prison in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where the warden refused to let media visit him, saying it would be a security concern and threaten orderly operations. Northington was recently transferred to a prison in another state.

Nearly every letter he writes starts with Assalamu-Alaikum. He talks about passing the GED and writing a book. He says the scans explain why he “couldn’t grab it” in school, that they show why he didn’t perform well and that he has to strain the parts of his brain that are working when he’s focusing. He also says that every day, he wonders about his appeal.

The bioethics report provides little resolution with regard to using scans – it states that the outcome for the defendants have been mixed while avoiding criticism of the science. Though Lee, the executive director of the Bioethics Commission, said there’s an expectation now for both the prosecutors and defense lawyers to consider how brain scans can help them present the best case possible.

Meanwhile, the federal government is pumping millions of dollars into fMRI research on mental diagnoses, partly in anticipation of the judicial system benefitting from it.

Everyone who has a stake in the science is hoping the scans will some day provide an unbiased truth. But there is a systematic problem because the law needs finality, while science relies on continued research. And for now, there is no way to see intention in the scans – there is no record of a crime, of innocence, of morality, of honesty. Behavioral brain scans are as objective as their interpreters.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion