Other Edens, inspired by the set of giant greenhouses on a derelict clay pit that have become the most successful tourist attraction in Cornwall, could soon sprout up in an English motorway service station, a Tasmanian warehouse, a Chinese docklands and among the giant sequoia trees of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the US.

“We’re not in the business of building theme parks, we’re in the business of building hope, inspiration and leadership,” said Sir Tim Smit, co-founder of the original Eden Project, launching Eden Project International, which aims to recreate not just the tourist bonanza but its environment consciousness-raising mission around the globe.

“We’re looking to create at least one Eden on every continent on Earth except Antarctica – and that’s because we’re already working on ideas for a centre in Tasmania looking at the Antarctic. That one is going to be fantastic: it will be in a warehouse, and it could be life-threatening – if you don’t grease up properly and dress warmly enough, the low temperatures and the ferocity of the wind could kill you.

“We want to create oases of change, which other people will want to emulate, which then become a transformative effect … We shouldn’t be sanctimonious about the problems that face the world, it’s not a question of wearing a hair shirt and punishing ourselves. We should be saying: look how cool the world could be. Our job is to create a fever of excitement about the world that is ours to make better.”

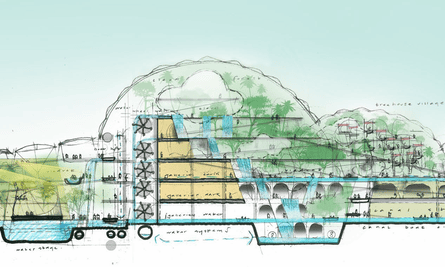

Plans for new centres at three sites in China, and in Australia and New Zealand, are being worked on with Grimshaw Architects, which designed the biomes in Cornwall. However, Smit promised: “It will be more than domes – in fact, I bloody well hope there will be very few domes, I’m too old to want to do a replica.”

As the fame of the Cornish centre spread, Smit said, he was bombarded with proposals from Britain and overseas for recreating the Eden effect in other deprived areas. “Mostly they just wanted a Tussauds waxworks with a bolt-on ethical conscience,” he said. “That’s not our thing.”

As well as the overseas projects, the foundation is working on several UK projects, including one on the river Foyle in Derry linking three old walled gardens (“one Catholic, one Protestant, one state-owned – we’re treading very carefully there,” Smit said) and one in the north of England.

Another is at an advanced stage of planning: what Smit promises will be “the best motorway service station in the world” at junction 27 of the M5, linked to Tiverton Parkway, where the plan is that visitors will arrive by train and hire electric cars to explore the surrounding countryside. “We’re on the cusp of a revolution in transport: within five to eight years I believe all major transport will be electric. The government is so far behind the ball with the 2040 thing that it’s laughable.”

The most daunting challenge is undoubtedly China, whose environmental record during its surge towards industrial development is generally seen as dismal. However, Smit is bullish about Eden’s future there. He says President Xi Jinping wants an improved environment as part of his legacy, younger industrialists he meets are ardent for change, and the country has planted more trees in the last two years than the rest of the world.

“All the party political chiefs I meet are embracing environmental change as if their lives depended on it – which, when you think about it, is pretty close to the knuckle,” Smit said.

Construction is scheduled to start this year on Eden Qingdao, in the port city on the east coast, on the theme of water and its importance for life. A feasibility report is complete for the city of Yan’an – the place Mao Zedong’s Long March came to an end. The plan is to transform a blighted valley just outside the city into a showcase for agriculture, craft and education. The third proposal is for the Sheng Lu vineyard in Beijing, a city regularly cloaked in an opaque fog of pollution.

Since the Eden Project opened in 2001 at a cost of £141m, including £56m from the Millennium Lottery fund, it has had more than 19 million visitors, generated an estimated £1.7bn for the region and several times been voted the UK’s best visitor attraction. It has drawn visitors by the million away from the traditional coastal hotspots into a post-industrial inland area that had been one of the most deprived parts of Britain.

The giant domes, which recreate different climate zones of the world, including a rainforest – and this summer go beyond Earth’s confines with a season of space-themed events – was an instant success, attracting more than double the projected numbers. However, it hit a bump in 2012/13 when numbers crashed because of bad weather and the rival attraction of the London Olympics. Cost-cutting, redundancies and restructuring followed, and Smit, knighted in 2013, stepped down later that year as chief executive.

Annual visitor numbers, bolstered by very successful Christmas events, have been increasing again over the last four years, climbing back above 1 million in 2016 for the first time since 2011, helping to bring in a cash surplus of more than £1.6m.

David Harland, who was Eden Project’s executive director and becomes chief executive of the new foundation, said it had been set up so that its success or otherwise would not affect the fortunes of the Cornwall centre.

“If we fail, we fail,” Smit, who becomes executive chairman, said cheerfully. “I’m quite prepared to fail, but I don’t think we will. Trust begets trust.”